Surprised By Hope Part 7: Resurrection

Well, friends, I'm afraid I'm going to have to end this series. Not because there's nothing more to say. Rather, these posts are pretty labor intensive, and I'm not sure I'm going to have the time to continue them any longer. To those that have accompanied me on the journey--both those who commented and those who did not--I owe you my deepest thanks. I wish there were more time to deeply explore some of the issues that have arisen in the past few weeks. Perhaps there will be at some point.

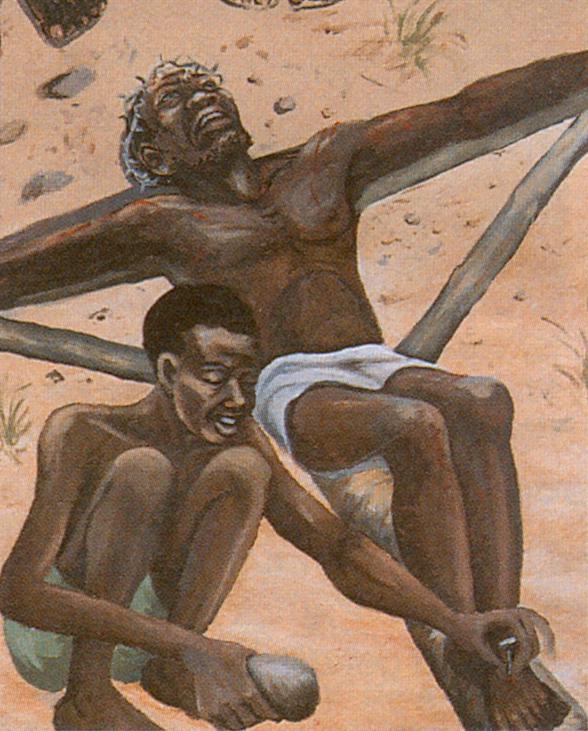

Well, friends, I'm afraid I'm going to have to end this series. Not because there's nothing more to say. Rather, these posts are pretty labor intensive, and I'm not sure I'm going to have the time to continue them any longer. To those that have accompanied me on the journey--both those who commented and those who did not--I owe you my deepest thanks. I wish there were more time to deeply explore some of the issues that have arisen in the past few weeks. Perhaps there will be at some point.Part 7 seemed to be the perfect one on which to end this series (for those of you who are into Jewish numerology at least...). Also, it seemed right to post on this particular topic on Resurrection Sunday. Today, Christians everywhere rejoice in the fact that the tomb is empty, and that we worship the risen and exalted messiah, Jesus.

In terms of apologetics for the truth of the resurrection I will give only a few brief comments--here I am drawing heavily upon Wright's work. My hunch is that few readers of this blog doubt the historicity of this event, but these things are still worth mentioning. First, those that would doubt the truth of the bodily resurrection of Christ must explain the historical (and sociological) curiosity of the early Christian movement. If Jesus did not actually rise from the dead, why would his disciples have continued to proclaim him as the messiah? A crucified Jewish would-be messiah in the first century was a FAILED messiah. This point cannot be made too strongly, and there are plenty of historical examples to support it. The followers of that would-be messiah had two options: a) disband and forget the hope of liberation that the 'messiah' seemed to offer, or b) elect a new messianic candidate from within who would continue the cause of liberation. Curiously, the first Christians did neither of these things, instead proclaiming that Jesus had BODILY risen from the dead. Wright and others argue vehemently that such a proclamation is historically inconceivable unless Jesus actually did rise.

A second and very convincing argument for the truth of the resurrection accounts in the gospels is that women were the first witnesses of the event. In Part 6, I mentioned briefly the second class status afforded women in Jewish society. They were not allowed to testify in court--their recounting of events would have been worthless for legal purposes. Such a situation begs the question: If the evangelists were trying to author a convincing fiction and pass it off as history, why in the world would they have written women as the leading actresses of their accounts? It would have convinced no one. The only explanation for the gospel accounts reading as they do is that they are historically accurate.

So, having established the facticity of the gospel accounts, what can we say about how the disciples understood the event itself? What did it mean within the larger schema of Jewish eschatology? Here the road is a bit bumpier, and I will again recommend reading Surprised By Hope for yourself if you want to get a clearer picture. For our purposes, an all-too-brief summary will have to suffice.

First, most Jews expected a resurrection to occur (save the Sadducees); everyone knew that Yahweh would one day resurrect all people for judgment in anticipation of/preparation for the new heavens and new earth. Let me be clear, all expectation in this regard had an end of the world referent. For Jesus' disciples to claim that their Lord had been raised from the dead in the middle of history would have been a novel invention indeed (were it not true). So what did it mean? For Paul, the answer is clear.

It meant that death had been defeated; it meant that Yahweh's new creation had already been inaugurated in the person of Jesus.

Jesus was, in this sense, the "truly human one." He was the lone example of what human life in God's perfect new creation would look like. He was the person in whom the future was caught up in the present. Notice that there is nothing that can be 'spiritualized' about Jesus' resurrection. It was not another way of referring to life after death in another place. Nor was it an interesting description of an intense private spirituality. Rather it was the prototype for life after life after death on earth (this is Wright's way of putting the matter, and I think it's spectacular).

So what should we make of the fact that God's new creation has been set loose in the person of Jesus Christ? I suggest the most appropriate response is to find out how we can get in on the action. After all, if there are two types of creation going on all around us--one that is subject to death and decay and another that bears the beauty of the risen Christ--it would seem logical to shoot for the latter. It is, therefore, our privilege and pleasure to be "in Christ" in this way--that we reflect the agenda of God's certain and conclusive future redemption for the entire cosmos in the present.

Or, as Paul puts it, "If anyone is in Christ [there is] a New Creation!! Everything old has passed away; behold! everything has become new."

*****

So what does all of this mean in terms of practical action? How does a belief in the present power of new creation affect the things that are said and done on an every day basis? I'd be lying if I said I had ready made answers to these questions. What I can do is offer some thoughts I've had about being a Christian in this generation--especially since reading this book. Much of this might not strike you as novel, but it is what it is....

I've thought long and hard about the ways in which being "in Christ" should make me different from any other person walking down the DC streets. What should set me apart? What would cause people to recognize the surprising and beautiful existence of new creation in the middle of history when it was on display in my life? What would cause people to be persuaded that a commitment to Christ is anything more than a personal spiritual add-on to the existing status quo?

First, I think my generation has stopped asking the question "is it right?" and replaced it with, "does it work?" It is the generation of the postmodern pragmatist, concerned more with the agenda of human advancement and advantage than the characteristics of new creation. Therefore, I need to remember that "Does it work" always serves the cause of the powerful (they define what 'works' and what doesn't) and to take up the cause of those who are casualties of that agenda. My operating paradigm for action must be rooted in "is it right?".

Second, I need to learn to be loving. I need to resist the tendency to redefine love in terms of what I consider to be possible--to remake love in my own image, if you will. I need to give up my self perceived need to be right as a matter of course, realizing that "the right" are not listed amongst the blessed in Jesus economy.

Like I said, nothing particularly new. These are just a couple of things I've been kicking around and trying to put into practice since reading this book. Feel free to add your own to the list of 'what new creation looks like in the 21st century.'

To all: Happy Resurrection Day. HE IS RISEN!

Labels: Surprised By Hope, Theological Musings